A year with Emacs

After a decade of exclusively using Vim for all my text editing, I decided to explore the other side of the barricade and see what the eternal adversary is doing. Ever since that day, I live in Emacs.

Motivation

Why would I commit such a heinous crime? After ten years, I came close to hitting my peak knowledge about Vim. Of course, nobody can claim to truly know Vim in its full depth but I got to the point where the learning curve slowed to a deadly pace and new tricks just slightly adjust your approach when solving obscure scenarios. The only real game-changer yet to be conquered was plugins development. I tried but I dislike VimL as a language for writing code and thus I have no intention of doing so.

On the other hand, I am fascinated by the functional programming paradigm and Lisp in particular. This alone, was a strong enough impulse for migrating to Emacs. I won’t hit the ceiling regarding custom package development.

Also, I came to realize, that my Vim workflow is different than for most other users (at least in my social circle). Everyone seems to have a shell-centric approach, find-ing, grep-ing, cat-ing their way through a project, and then opening the intended file in Vim, editing, and closing. I do the same thing when it comes to searching within a project but I do it in a separate terminal. When it comes to Vim, I start it once, do everything from within, and then close it after six months when a new Fedora is released and I need to upgrade. If it reminds you of something, it’s Emacs.

There is also a couple of tempting Emacs features but about them later.

Preview

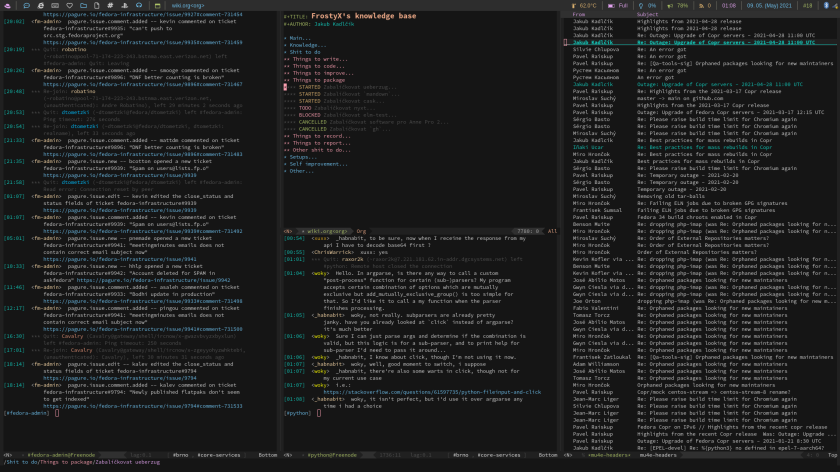

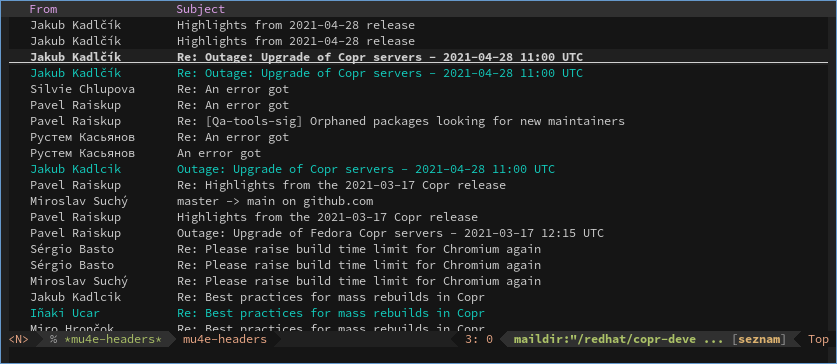

On my triple-monitor setup, two of the screens are dedicated to maximized Emacs frames. This is how my PIM screen looks like.

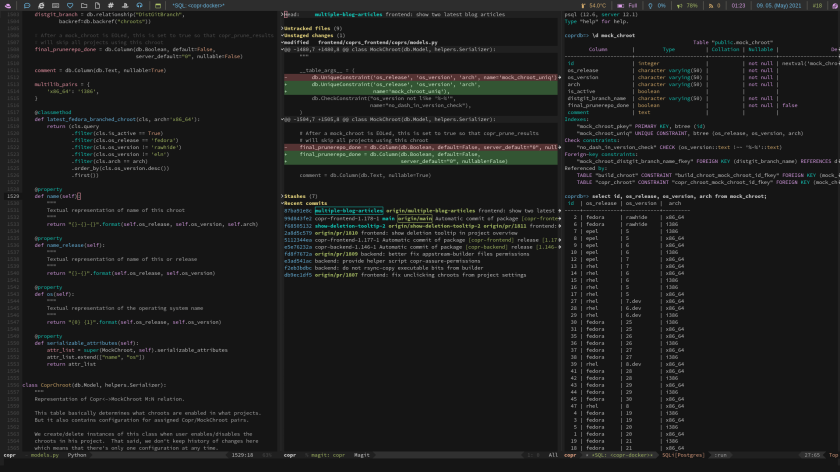

The main monitor is designated for development.

The goal was to make the development setup identical to my previous Vim configuration.

Misconceptions

Due to my heavy addiction to Vim keybindings and modal editing, a non-negotiable requisite was a decent Vim emulator inside of Emacs. As it turned out, Evil is not only a great name but also a great piece of software. However, it is often marketed in a way, that you don’t have to learn Emacs key bindings at all. This was a big selling point for me, that however, turned out not to be true.

Yes, Evil is probably the best Vim emulator out there and provides

support for every Vim feature that I know of. The thing we need to

realize is that Emacs has a much broader scope than just text editing. It is

more of an application platform rather than an editor. Naturally, there

cannot be any Vim keybindings for things that are beyond its abilities.

Don’t worry though. You can get far enough by learning M-x for running commands,

M-: for Elisp evaluation, and by defining custom key bindings.

Another unpleasant surprise was that my .vimrc was completely useless for the migration. For some reason I expected Evil to parse and apply my current Vim configuration, and even use the Vim plugins I had installed. You can laugh at me now. That, of course, is not possible but in the end, it cost me just a couple extra days of fieldwork. Most of the popular Vim plugins have authentic Emacs clones.

Here is a migration table based on the plugins that I use.

| Vim plugin | Emacs alternative | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Vundle.vim | use-package | Emacs has a built-in package manager |

| vim-fugitive | magit | |

| vim-rhubarb | browse-at-remote | |

| vim-sleuth | dtrt-indent | |

| vim-fugitive-pagure | browse-at-remote | |

| nerdtree | neotree | Use dired instead, trust me |

| fzf.vim | helm | Much more then just fzf |

| tcomment_vim | evil-commentary | |

| matchit | evil-matchit | |

| delimitMate | smartparens | |

| Vim-Jinja2-Syntax | jinja2-mode | |

| vim-markdown | markdown-mode | |

| syntastic | company-mode | |

| vimwiki | org-mode | |

| goyo.vim | writeroom | |

| base16-vim | base16-theme | |

| vim-css-color | rainbow-mode |

For migrating the Vim settings themselves, you will need to read

the manual (or my Emacs config) because it is not possible to cover

here. However, I still think it would be pretty amazing if we could

write some package that would parse ~/.vimrc and print Elisp code for doing

the same thing in Evil. Anyone wants to collaborate on that?

So far, this whole thing may seem like a chore with no benefits. Well, buckle up.

IDE on steroids

During the last year, I was basically living in Emacs. At first, it replaced only my IDE but then Emacs quickly became my RSS aggregator, task manager, IRC client, Email client and kept consuming all standalone programs. All of them now share the same configuration language, keybindings, theme, etc. Thanks to Evil, those keybindings happen to be Vim-like.

I love this great paradox that thanks to Emacs, I have more Vim in my life.

As a consequence, all of these applications are integrated together and it is possible to seamlessly create tasks based on emails, paste short pieces of code into IRC, viewing a git history and jumping to the changed files, sending a SQL query to a coworker via email (the possibilities are endless) without ever touching a mouse or even needing the system clipboard. It’s all in the Vim/Evil registers, so only yanking and pasting like a true gentleman.

For the past ten years, I was trying to achieve such a setup using a combination of Tmux, Vim, Mutt, Weechat, and other tools but the experience was vastly different. No matter what, it felt like using several single-purpose programs, each of them isolated in its own bubble and with no way of cooperating with each other.

Literate config

Since the operating system becomes just a bootloader for Emacs (and maybe a web browser), it means that every application is used and configured within Emacs. Luckily for us, it has the best configuration apparatus ever invented. Remember the literate programming paradigm, which was only briefly noted in a school curriculum as a slow, retarded cousin of procedural and object-oriented paradigms? It turns out to be pretty fucking awesome after all.

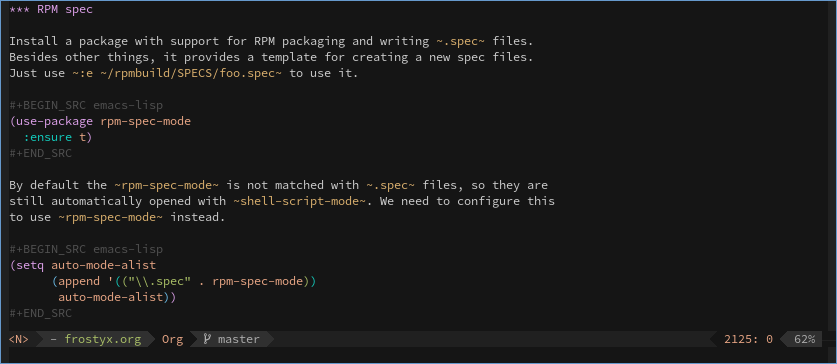

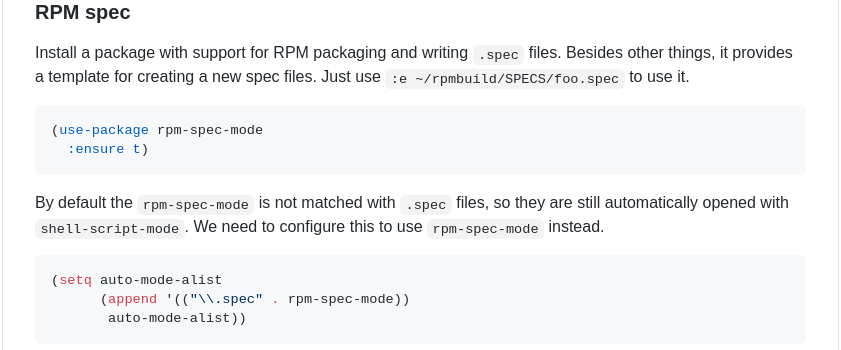

Emacs configuration can be written in an Org-mode document and can look like a book explaining various features, settings, and customizations, with thorough code sample coverage. Quite literally because the document can be exported as a web page or stylized PDF. See my config on GitHub to get the idea.

The Org configuration file renders beautifully on GitHub and possibly other Git forges.

Email client, finally

Accessing email in the terminal was a recurring nerd-fantasy of mine ever since I started using GNU/Linux in 2008. Up until very recently, all my attempts of achieving this holy grail rendered futile.

Finally, I could cross this off my list thanks to a combination of mbsync and mu4e. There is nothing much to say. It is an email client. Inside of Emacs. But for some undefinable reason, it is the greatest thing ever invented.

The hardest part isn’t the email client configuration itself but rather synchronization with IMAP (in the age of two-factor authentication). If you are interested, I wrote a whole article on this topic - Synchronize your 2FA Gmail with mbsync

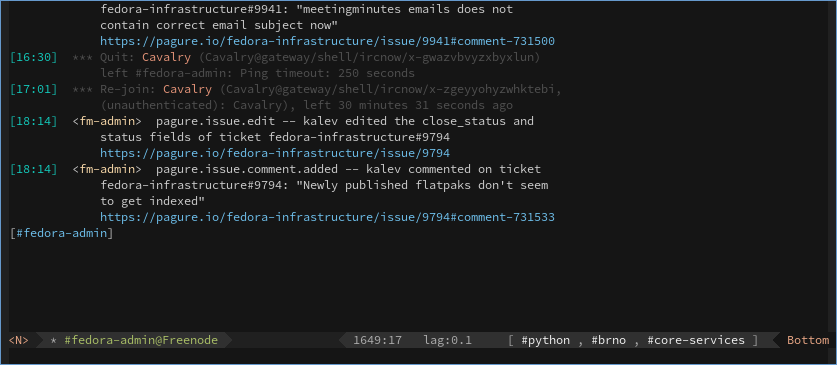

IRC with Vim keybindings

Weechat is an exceptionally good piece of software but to be honest I was aching to replace it for quite some time. There just wasn’t a better alternative. My frustrations were caused solely by two pitfalls.

Copy-pasting from Tmux + Weechat combo is god-awful and borderline

psychotic. Imagine Weechat window vertically split into multiple

panes. Since it is an application running in a single terminal

window, the terminal has no perception of any separation, splits, or

panes that are displayed within. Selecting a multi-line text with a

mouse, therefore, isn’t limited to the desired pane but rather to

everything that stands in the way. The copied text then contains

mixed messages from multiple chat windows, ASCII symbols that were

used as separators, timestamps, and all. Copy-pasting from Tmux + Weechat is

quite alright if you are aware of

rectangle selection.

Apart from this, I was always uncomfortable with Weechat’s approach to generated configuration files. Even though it is generally looked at as a feature allowing to configure Weechat from within itself, saving its current state, and eliminating the need to edit the configuration file in its written form. I never grew accustomed to this paradigm and prefer to edit configuration files by hand.

Circe is in many aspects inspired by Weechat and inherits some of its traits while eradicating the pitfalls beyond perfectly. Circe chat windows are standard Emacs buffers with full Vim emulation and shared registers with the whole ecosystem. Lisp configuration also surpasses anything else we could wish for.

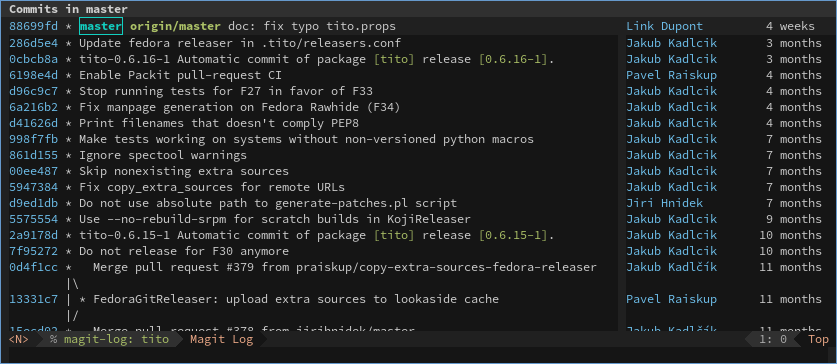

Magit

Magit is one of the tools that I would refuse to believe I might

enjoy using. What’s the point with git diff, git add, and git

commit commands already hard-wired in my muscle memory in such a

manner, that executing them resembles more of an involuntary spasm

rather than typing words.

Yet, I am forever hooked to Magit now. One shall never stage a whole

file before checking its git diff (because of possible unwanted

changes). That’s two commands per file, all the time. Whereas Magit

provides a compact view of files and their changes at once. Staging a

whole file or its chunks is then a matter of pressing one key.

Committing, pushing, iterating over a series of commits, blaming,

rebasing, everything is a bit more convenient. I still use the git

command for more complicated operations though.

Emacs in browser

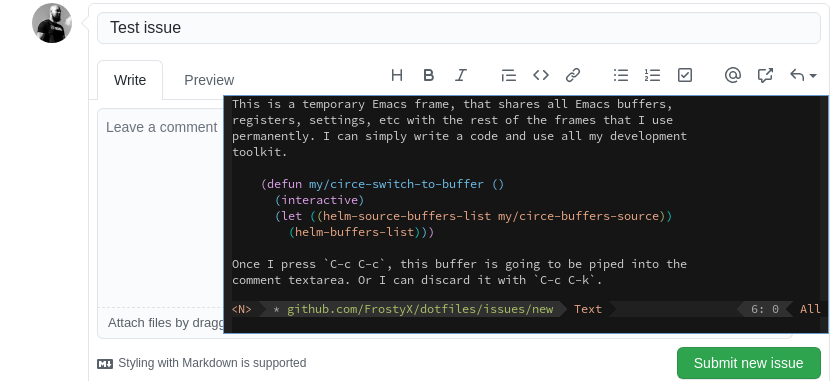

As a software engineer, I frequently engage in technical discussions on various git forge sites (such as GitHub, Pagure.io), and Reddit. Consequently, I write comments containing pieces of code on daily basis (either being code reviews and suggestions, bug reproducers, or proposed solutions).

My workflow usually involved firing up the good ol’ text editor, pre-formatting the code, and copy-pasting it into the comment. Omitting this step and editing the code directly in the web browser is doable but especially adjusting whitespace sucks so much, that you eventually end up spawning a text editor and regretting you didn’t do it in the first place.

Edit with Emacs is a handy convenience tool that provides a key binding to make a temporary Emacs frame with the contents of your textarea. After you are done, it pipes the output back to the browser.

There is nothing special about this functionality in regards to Emacs and there surely is a plugin compatible with any text editor. On the contrary, I think Emacs lags behind Neovim in this scenario, which is able to transform a textarea into a Neovim instance directly in the web browser thanks to Firenvim.